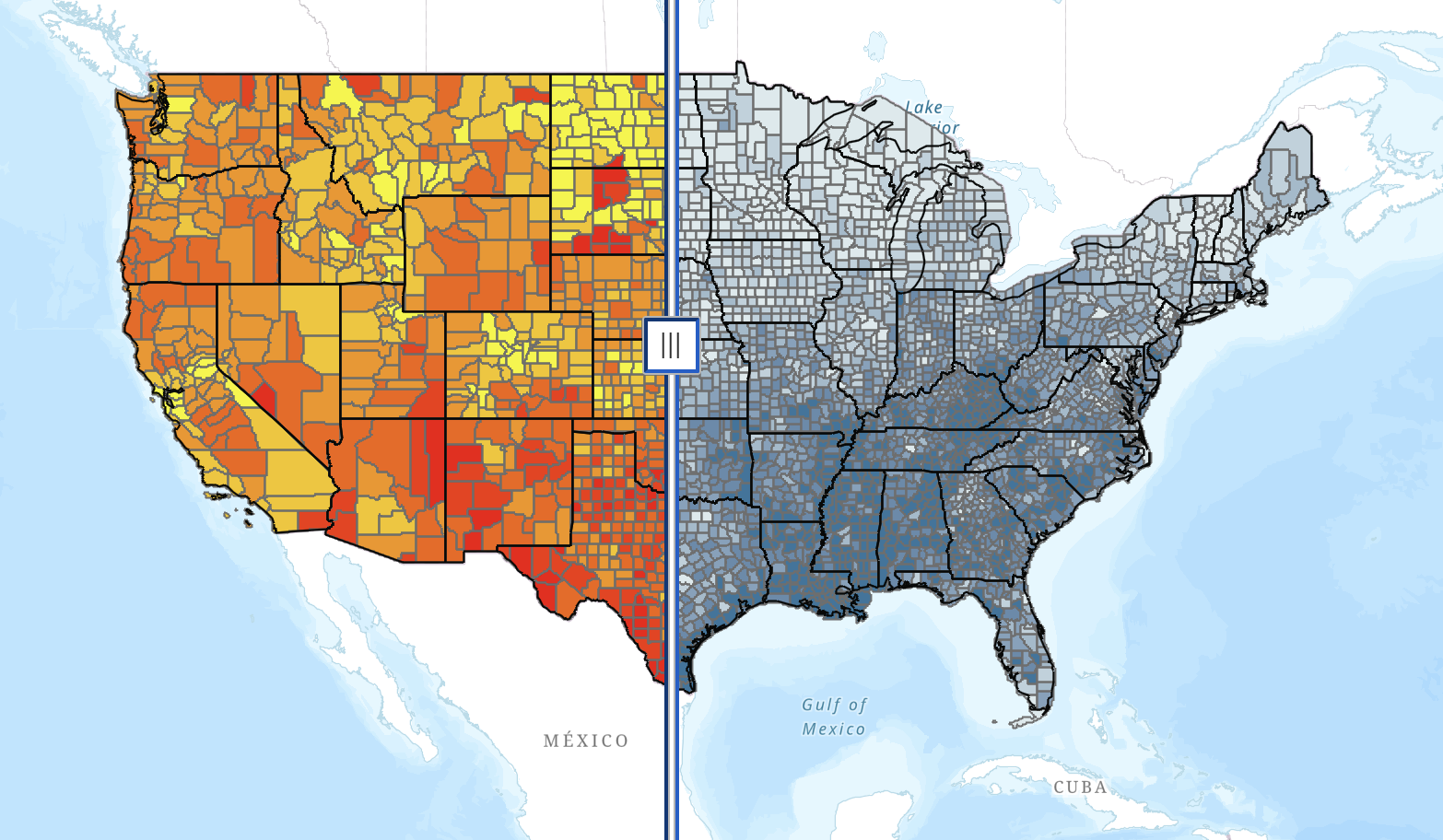

Imagine driving up to four hours to get to the nearest grocery store. For many families living in Navajo Nation, this is the reality to access nutritious food. Although the entirety of Navajo Nation is roughly the same size as Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire combined, the area has only 13 grocery stores and falls outside the regions reliably covered by other food recovery organizations.The Farmlink Project has been honored to be able to serve the Navajo Nation’s residents with the help of our partners for a year and a half.

.png)

In early February, our creative team leads, Kate and Owen, took a trip to the upper northeast portion of Navajo Nation, the Huerfano Chapter House. Below is a delivery recount from Kate listening to the people of this community and the challenges they have faced:

It's 6am in Farmington, New Mexico. I had flown in the night before from New York, and my co-lead of the Creative PIllar, Owen, had flown in from Los Angeles. Our destination was the Navajo Nation, to help with the delivery of mixed produce and learn more about the day-to-day lives of people in this community, where consistent access to nutritious food isn’t always possible. We were driving through San Juan County, which saw a rate of 16.5% food insecurity in 2019, or 20,810 people who lacked consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. We could only imagine that the pandemic since then has done nothing to help this harrowing statistic.

.jpg)

There is nothing for miles except heavy snow falling, coating the miles of desert. We didn’t realize it could snow here. After about 40 minutes driving through nothing but flat land and snow-covered cacti, we pulled up to the Huerfano Chapter house, a small, community-run building where locals host meetings, gatherings and town halls. This group has been here since 1956. Everyone has a role in unloading the 20ft truck full of produce. After about two hours, all the pallets are stacked neatly in the parking lot, ready to be picked up by those who need it. 40,000 pounds of produce looks massive when it's all boxed up, standing in the snow waiting to be picked up. Across one of the pallets, an off-center sticker reads: “DUMP,” indicating that all 40,000 pounds was going to be sent to the landfill.

.jpg)

These 40,000 pounds boast a wide array of vegetables, including snap peas, squash, bell peppers, broccoli, corn, melons, and more, indistinguishable from what you would buy at a high-end grocery store like Whole Foods. This perfectly usable, fresh, top-quality produce was turned away because the intended grocery store had over ordered. Thankfully, Farmlink’s Hunger & Outreach Team received a call about the rejected load and nimbly rerouted it all here, where it could reach 1500 people hailing from across 90 square miles in and around Navajo Nation.

At 1:00pm we looked outside and to our surprise, saw cars full of people lining up to pick up their boxes. While the snowfall lightened and Chapter House leader Ben Woody greeted the incoming community members, seven Chapter volunteers, Owen and I squeezed the boxes containing each kind of produce into trunks, over car seats and onto laps. We were greeted by fathers, mothers, children, grandparents, friends, and neighbors who were eager to share this food with their loved ones.

While loading, Owen and I spoke with the community members waiting in line. Irene, who lives on the reservation with her family and many animals including goats, horses and dogs, has to drive nearly 50 miles to get to the closest grocery store. If such a journey was cost-prohibitive in early February of this year, I shudder to think of what the price of that would be now, given the unprecedented rise in gas and oil prices since the invasion of Ukraine. A roundtrip journey to the grocery store would be unaffordable for her, but if it were not for the Huerfano Chapter House distribution made possible by Farmlink, she would have no other choice. Irene told us that this food distribution cut her travel time in half, and although it did not solve all of her problems, it was a big help to her and her family. She explained, “that’s why I’m out here, in the rain, in the snow because I thought this would help my family. It helps a lot.”

According to Ben Woody, most people have to travel over 70 miles to get access to produce. “I do this because I want my people to be in a safe environment, I don’t want anyone going hungry. I also provide a lot of technical support with how to [cook] a lot of the produce that we get- sometimes I actually just go on google and get brochures on how to [prepare] a lot of these recipes [so that] none of the produce we don’t know how to prepare goes to waste,” Woody said. “The main thing right now is hopefully this program will continue and that we get more assistance in the future because we really need it,” Woody said.

As the car line slowly died down, we took heart in the realization that what we did today was just one twelfth of what The Farmlink Project does every week. At the same moment we were talking with Irene, who was awaiting a robust array of nourishing produce, others across the country were wondering where their next meal was going to come from. We left with a sense of awe at the scale of Farmlink’s support of the region and questions about why so many pockets of our country, where over 35 million people are food insecure, continue to experience unthinkably high barriers to access of such a basic need as fresh produce. While discouraged by the stories of so many like Irene, we left fueled with renewed motivation to ensure that the Navajo Nation continues to receive all the fresh produce they needed, and are being seen. As Farmlink works long nights and perseveres to navigate the food supply chain, we hope to continue to serve communities in need and get food to where it is needed most.

< Back

Imagine driving up to four hours to get to the nearest grocery store. For many families living in Navajo Nation, this is the reality to access nutritious food. Although the entirety of Navajo Nation is roughly the same size as Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire combined, the area has only 13 grocery stores and falls outside the regions reliably covered by other food recovery organizations.The Farmlink Project has been honored to be able to serve the Navajo Nation’s residents with the help of our partners for a year and a half.

.png)

In early February, our creative team leads, Kate and Owen, took a trip to the upper northeast portion of Navajo Nation, the Huerfano Chapter House. Below is a delivery recount from Kate listening to the people of this community and the challenges they have faced:

It's 6am in Farmington, New Mexico. I had flown in the night before from New York, and my co-lead of the Creative PIllar, Owen, had flown in from Los Angeles. Our destination was the Navajo Nation, to help with the delivery of mixed produce and learn more about the day-to-day lives of people in this community, where consistent access to nutritious food isn’t always possible. We were driving through San Juan County, which saw a rate of 16.5% food insecurity in 2019, or 20,810 people who lacked consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. We could only imagine that the pandemic since then has done nothing to help this harrowing statistic.

.jpg)

There is nothing for miles except heavy snow falling, coating the miles of desert. We didn’t realize it could snow here. After about 40 minutes driving through nothing but flat land and snow-covered cacti, we pulled up to the Huerfano Chapter house, a small, community-run building where locals host meetings, gatherings and town halls. This group has been here since 1956. Everyone has a role in unloading the 20ft truck full of produce. After about two hours, all the pallets are stacked neatly in the parking lot, ready to be picked up by those who need it. 40,000 pounds of produce looks massive when it's all boxed up, standing in the snow waiting to be picked up. Across one of the pallets, an off-center sticker reads: “DUMP,” indicating that all 40,000 pounds was going to be sent to the landfill.

.jpg)

These 40,000 pounds boast a wide array of vegetables, including snap peas, squash, bell peppers, broccoli, corn, melons, and more, indistinguishable from what you would buy at a high-end grocery store like Whole Foods. This perfectly usable, fresh, top-quality produce was turned away because the intended grocery store had over ordered. Thankfully, Farmlink’s Hunger & Outreach Team received a call about the rejected load and nimbly rerouted it all here, where it could reach 1500 people hailing from across 90 square miles in and around Navajo Nation.

At 1:00pm we looked outside and to our surprise, saw cars full of people lining up to pick up their boxes. While the snowfall lightened and Chapter House leader Ben Woody greeted the incoming community members, seven Chapter volunteers, Owen and I squeezed the boxes containing each kind of produce into trunks, over car seats and onto laps. We were greeted by fathers, mothers, children, grandparents, friends, and neighbors who were eager to share this food with their loved ones.

While loading, Owen and I spoke with the community members waiting in line. Irene, who lives on the reservation with her family and many animals including goats, horses and dogs, has to drive nearly 50 miles to get to the closest grocery store. If such a journey was cost-prohibitive in early February of this year, I shudder to think of what the price of that would be now, given the unprecedented rise in gas and oil prices since the invasion of Ukraine. A roundtrip journey to the grocery store would be unaffordable for her, but if it were not for the Huerfano Chapter House distribution made possible by Farmlink, she would have no other choice. Irene told us that this food distribution cut her travel time in half, and although it did not solve all of her problems, it was a big help to her and her family. She explained, “that’s why I’m out here, in the rain, in the snow because I thought this would help my family. It helps a lot.”

According to Ben Woody, most people have to travel over 70 miles to get access to produce. “I do this because I want my people to be in a safe environment, I don’t want anyone going hungry. I also provide a lot of technical support with how to [cook] a lot of the produce that we get- sometimes I actually just go on google and get brochures on how to [prepare] a lot of these recipes [so that] none of the produce we don’t know how to prepare goes to waste,” Woody said. “The main thing right now is hopefully this program will continue and that we get more assistance in the future because we really need it,” Woody said.

As the car line slowly died down, we took heart in the realization that what we did today was just one twelfth of what The Farmlink Project does every week. At the same moment we were talking with Irene, who was awaiting a robust array of nourishing produce, others across the country were wondering where their next meal was going to come from. We left with a sense of awe at the scale of Farmlink’s support of the region and questions about why so many pockets of our country, where over 35 million people are food insecure, continue to experience unthinkably high barriers to access of such a basic need as fresh produce. While discouraged by the stories of so many like Irene, we left fueled with renewed motivation to ensure that the Navajo Nation continues to receive all the fresh produce they needed, and are being seen. As Farmlink works long nights and perseveres to navigate the food supply chain, we hope to continue to serve communities in need and get food to where it is needed most.

Navajo Nation

Imagine driving up to four hours to get to the nearest grocery store. For many families living in Navajo Nation, this is the reality to access nutritious food. Although the entirety of Navajo Nation is roughly the same size as Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire combined, the area has only 13 grocery stores and falls outside the regions reliably covered by other food recovery organizations.The Farmlink Project has been honored to be able to serve the Navajo Nation’s residents with the help of our partners for a year and a half.

.png)

In early February, our creative team leads, Kate and Owen, took a trip to the upper northeast portion of Navajo Nation, the Huerfano Chapter House. Below is a delivery recount from Kate listening to the people of this community and the challenges they have faced:

It's 6am in Farmington, New Mexico. I had flown in the night before from New York, and my co-lead of the Creative PIllar, Owen, had flown in from Los Angeles. Our destination was the Navajo Nation, to help with the delivery of mixed produce and learn more about the day-to-day lives of people in this community, where consistent access to nutritious food isn’t always possible. We were driving through San Juan County, which saw a rate of 16.5% food insecurity in 2019, or 20,810 people who lacked consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. We could only imagine that the pandemic since then has done nothing to help this harrowing statistic.

.jpg)

There is nothing for miles except heavy snow falling, coating the miles of desert. We didn’t realize it could snow here. After about 40 minutes driving through nothing but flat land and snow-covered cacti, we pulled up to the Huerfano Chapter house, a small, community-run building where locals host meetings, gatherings and town halls. This group has been here since 1956. Everyone has a role in unloading the 20ft truck full of produce. After about two hours, all the pallets are stacked neatly in the parking lot, ready to be picked up by those who need it. 40,000 pounds of produce looks massive when it's all boxed up, standing in the snow waiting to be picked up. Across one of the pallets, an off-center sticker reads: “DUMP,” indicating that all 40,000 pounds was going to be sent to the landfill.

.jpg)

These 40,000 pounds boast a wide array of vegetables, including snap peas, squash, bell peppers, broccoli, corn, melons, and more, indistinguishable from what you would buy at a high-end grocery store like Whole Foods. This perfectly usable, fresh, top-quality produce was turned away because the intended grocery store had over ordered. Thankfully, Farmlink’s Hunger & Outreach Team received a call about the rejected load and nimbly rerouted it all here, where it could reach 1500 people hailing from across 90 square miles in and around Navajo Nation.

At 1:00pm we looked outside and to our surprise, saw cars full of people lining up to pick up their boxes. While the snowfall lightened and Chapter House leader Ben Woody greeted the incoming community members, seven Chapter volunteers, Owen and I squeezed the boxes containing each kind of produce into trunks, over car seats and onto laps. We were greeted by fathers, mothers, children, grandparents, friends, and neighbors who were eager to share this food with their loved ones.

While loading, Owen and I spoke with the community members waiting in line. Irene, who lives on the reservation with her family and many animals including goats, horses and dogs, has to drive nearly 50 miles to get to the closest grocery store. If such a journey was cost-prohibitive in early February of this year, I shudder to think of what the price of that would be now, given the unprecedented rise in gas and oil prices since the invasion of Ukraine. A roundtrip journey to the grocery store would be unaffordable for her, but if it were not for the Huerfano Chapter House distribution made possible by Farmlink, she would have no other choice. Irene told us that this food distribution cut her travel time in half, and although it did not solve all of her problems, it was a big help to her and her family. She explained, “that’s why I’m out here, in the rain, in the snow because I thought this would help my family. It helps a lot.”

According to Ben Woody, most people have to travel over 70 miles to get access to produce. “I do this because I want my people to be in a safe environment, I don’t want anyone going hungry. I also provide a lot of technical support with how to [cook] a lot of the produce that we get- sometimes I actually just go on google and get brochures on how to [prepare] a lot of these recipes [so that] none of the produce we don’t know how to prepare goes to waste,” Woody said. “The main thing right now is hopefully this program will continue and that we get more assistance in the future because we really need it,” Woody said.

As the car line slowly died down, we took heart in the realization that what we did today was just one twelfth of what The Farmlink Project does every week. At the same moment we were talking with Irene, who was awaiting a robust array of nourishing produce, others across the country were wondering where their next meal was going to come from. We left with a sense of awe at the scale of Farmlink’s support of the region and questions about why so many pockets of our country, where over 35 million people are food insecure, continue to experience unthinkably high barriers to access of such a basic need as fresh produce. While discouraged by the stories of so many like Irene, we left fueled with renewed motivation to ensure that the Navajo Nation continues to receive all the fresh produce they needed, and are being seen. As Farmlink works long nights and perseveres to navigate the food supply chain, we hope to continue to serve communities in need and get food to where it is needed most.

.png)

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)